Patriotism, Duty And Honor

The American people, North and South, went into the [Civil] war as citizens of their respective states, they came out as subjects … what they thus lost they have never got back. – H.L. Mencken

Our government is an agency of delegated and strictly limited powers. Its founders did not look to its preservation by force; but the chain they wove to bind these States together was one of love and mutual good office... Jefferson Davis

This entry is from A Rebel War Clerk's Diary at the Confederate States Capital by John Beauchamp Jones

May 7th, 1861

Col. R. E. Lee, lately of the United States army, has been appointed major-general, and commander-in-chief of the army in Virginia. He is the son of "Light Horse Harry" of the Revolution. The North can boast no such historic names as we, in its army.

May 7th, 1861

Col. R. E. Lee, lately of the United States army, has been appointed major-general, and commander-in-chief of the army in Virginia. He is the son of "Light Horse Harry" of the Revolution. The North can boast no such historic names as we, in its army.

“If certain minds cannot understand the difference between patriotism, the highest civic virtue, and office-seeking, the lowest civic occupation, I pity them from the bottom of my heart.”

- General P.G.T. Beauregard ~ C.S.A.

- General P.G.T. Beauregard ~ C.S.A.

~ General Pierre Gustave Toutant Beauregard C.S.A. ~

"The Government of the Confederate States has hitherto forborne from any hostile demonstration against Fort Sumter, in the hope that the Government of the United States, with a view to the amicable adjustment of all questions between the two Governments, and to avert the calamities of war, would voluntarily evacuate it." ~~ Beauregard in a dispatch to Anderson before the battle. Aides delivered messages to the island in hopes of avoiding conflict.

"By the authority of Brigadier General Beauregard, commanding the Provisional Forces of the Confederate States, we have the honor to notify you that he will open the fire of his batteries on Fort Sumter in one hour from this time." ~~ A message delivered by two of Beauregard's aides to Maj. Anderson. Beauregard would open fire at 4:30 a.m. April 12th, 1861.

"By the authority of Brigadier General Beauregard, commanding the Provisional Forces of the Confederate States, we have the honor to notify you that he will open the fire of his batteries on Fort Sumter in one hour from this time." ~~ A message delivered by two of Beauregard's aides to Maj. Anderson. Beauregard would open fire at 4:30 a.m. April 12th, 1861.

President Jefferson Davis ~ Confederate States of America

I worked night and day for twelve years to prevent the war, but I could not. The North was mad and blind, would not let us govern ourselves, and so the war came.

Jefferson Davis

Jefferson Davis

~ General Robert E. Lee ~

". . .a union that can only be maintained by swords and bayonets and in which strife and civil war are to take the place of brotherly love and kindness has no charm for me. I shall mourn for my country and for the welfare of mankind. If the union is dissolved and the government disrupted, I shall return to my native state and share the miseries of my people, and save in defense, will draw my sword on none."

~~~ General Robert E. Lee, C.S.A.

"Governor, if I had foreseen the use these people desired to make of their victory, there would have been no surrender at Appomattox, no, sir, not by me. Had I seen these results of subjugation, I would have preferred to die at Appomattox with my brave men, my sword in this right hand."

~~~ General Robert E. Lee, C.S.A. - as told to Texas ex-governor

“All that the South has ever desired was that the Union, as established by our forefathers, should be preserved, and that the government, as originally organized, should be administered in purity and truth.”---General Robert E. Lee, C.S.A.

~~~ General Robert E. Lee, C.S.A.

"Governor, if I had foreseen the use these people desired to make of their victory, there would have been no surrender at Appomattox, no, sir, not by me. Had I seen these results of subjugation, I would have preferred to die at Appomattox with my brave men, my sword in this right hand."

~~~ General Robert E. Lee, C.S.A. - as told to Texas ex-governor

“All that the South has ever desired was that the Union, as established by our forefathers, should be preserved, and that the government, as originally organized, should be administered in purity and truth.”---General Robert E. Lee, C.S.A.

~ Lieutenant General Wade Hampton ~

"If we were wrong in our contest, then the Declaration of Independence of 1776 was a grave mistake, and the revolution to which it led was a crime. If Washington was a patriot, Lee cannot have been a rebel."

Lt. General Wade Hampton, C.S.A.

Lt. General Wade Hampton, C.S.A.

~ Captain Raphael Semmes, C.S.N. ~

"With the exception of a few honest zealots, the canting hypocritical Yankee cares as little for our slaves as he does for our draught animals. The war which he has been making upon slavery for the last 40 years is only an interlude, or by-play, to help on the main action of the drama, which is Empire; and it is a curious coincidence that it was commenced about the time the North began to rob the South by means of its tariffs. When a burglar designs to enter a dwelling for the purpose of robbery, he provides himself with the necessary implements. The slavery question was one of the implements employed to help on the robbery of the South. It strengthened the Northern party, and enabled them to get their tariffs through Congress; and when at length, the South, driven to the wall, turned, as even the crushed worm will turn, it was cunningly perceived by the Northern men that 'No slavery' would be a popular war-cry, and hence, they used it."

Captain Raphael Semmes, C.S.N. August 5th, 1861

Captain Raphael Semmes, C.S.N. August 5th, 1861

~ General Patrick Cleburne ~

I am with the South in life or in death, in victory or defeat. I never owned a negro and care nothing for them, but these people have been my friends and have stood up to me on all occasions. In addition to this, I believe the North is about to wage a brutal and unholy war on a people who have done them no wrong, in violation of the Constitution and the fundamental principles of the government...We propose no invasion of the North, no attack on them, and only ask to be let alone. General Patrick R. Cleburne

~ Major General J.E.B. Stuart - Confederate States Cavalry ~

"I would rather be a private in Virginia's army than a general in any army that was going to coerce her."

~~ General J.E.B. Stuart, C.S.A.

~~ General J.E.B. Stuart, C.S.A.

" No Freed, I do not love bullets any better than you do; I go where they are because it is my duty, and I do not expect to survive the war.” Major General J.E.B. Stuart, C.S.A., in a response to his longtime bugler Private George Freed who remarked “General, I believe you love bullets.”

Major John Singleton Mosby

John Singleton Mosby on Sheridan's depredations in Virginia written well after the war: Contributed by, Valerie Protopapas

“After destroying all the wheat and corn in a country, to burn mills where there is nothing to grind is pure wantonness. All the barns were burned no matter whether there was forage in them or they were empty. The destruction of implements of husbandry to prevent the planting of crops simply because there is a possibility of their being useful to an enemy, can no more be justified than killing defenseless women and children. It is true that there is a chance that the crops that are allowed to be sown may be useful to the enemy; and it is equally true that if the war lasts long enough, as did the Thirty Years’ War, children may grow up, and women may become the mothers of soldiers. The injury inflicted is certain and permanent. There is only a possibility of its weakening the resources of the enemy; the benefit is too remote and contingent. The war did in fact, close before another crop could have been reaped in the Shenandoah Valley. I am judging by the principles that I wish myself to be judged.

“In his Memoirs General Sheridan repudiates the humane maxims of Grotius and Vattel, and lays down an ethical code for the government of armies in war that abolishes all distinctions heretofore recognized between combatant and noncombatant enemies. If the United States should adopt it, then Napoleon’s saying, “Scratch a Russian (and) you will find a Tarter,” will not apply alone to the subjects of the Czar. In contrast with these pitiless doctrines that suggest the picture of the Infernal Court and “The iron tears that rain down Pluto’s cheek,” are the humane rules of international law as expounded by Professor Twiss, of Oxford, in his work on Rights and Duties in Time of War.

“All damage, therefore, which is done to an enemy without any corresponding advantage accruing to the belligerent is an abuse of a natural right of the latter. Thus, indeed, a belligerent is entitled to capture all the property of an enemy which is calculated to enable him the better to carry on hostilities, and if he cannot carry it away conveniently, to destroy it. A belligerent, for example, may destroy all existing stores of provisions and forage, which he cannot conveniently carry away, and may even destroy the standing crops, in order to deprive his enemy of immediate subsistence, and so reduce him to surrender. But a belligerent will not be justified in cutting the olive trees and rooting up the vines; for that is to inflict desolation upon a country for many years to come, and the belligerent cannot derive any corresponding advantage therefrom. When the French armies desolated with fire and sword the Palatinate in 1674 and again in 1689, there was a general outcry throughout Europe against such a mode of carrying on war; and when the French Minister, Louvol, alleged that the object in view was to cover the French frontier against invasion from the enemy, the advantage which France derived from the act was universally held to be inadequate to the suffering inflicted, and the act itself to be, therefore, unjustifiable.

“A belligerent prince who should, in the present day, without necessity, ravage an enemy’s country with fire and sword, and render it uninhabitable, in order to make it serve as a barrier against the advance of the enemy, would be just regarded as a modern Attila.”

It must be remembered that after the war, Mosby worked tirelessly to achieve true reconciliation. He wished the wrongs - real and perceived - on BOTH sides consigned to oblivion. As such he "made up" with men like Sheridan. However, as the new century commenced, Mosby began to see the true nature of the government that had prevailed in the war. Part of that was the numerous times in which his efforts to fulfill duties of justice to which he was assigned by the government by which he had been employed were thwarted by members of that same government, usually resulting in him being demoted, removed and re-assigned to some other area at less pay. In 1910 when he refused to cover up the theft of money from the Indians in Oklahoma after being offered a $35,000 bribe, he was fired from the Department of Justice and set adrift without money or a position. Mosby managed to support himself by writing and lecturing (he was let go because he was "senile!"), but died in poverty in 1916. By that time, however, I believe that he had finally understood why the South went to war. In the last sentence of his memoirs published posthumously, he stated that if he could have saved the Confederacy "with this right arm," he would have done so.

“After destroying all the wheat and corn in a country, to burn mills where there is nothing to grind is pure wantonness. All the barns were burned no matter whether there was forage in them or they were empty. The destruction of implements of husbandry to prevent the planting of crops simply because there is a possibility of their being useful to an enemy, can no more be justified than killing defenseless women and children. It is true that there is a chance that the crops that are allowed to be sown may be useful to the enemy; and it is equally true that if the war lasts long enough, as did the Thirty Years’ War, children may grow up, and women may become the mothers of soldiers. The injury inflicted is certain and permanent. There is only a possibility of its weakening the resources of the enemy; the benefit is too remote and contingent. The war did in fact, close before another crop could have been reaped in the Shenandoah Valley. I am judging by the principles that I wish myself to be judged.

“In his Memoirs General Sheridan repudiates the humane maxims of Grotius and Vattel, and lays down an ethical code for the government of armies in war that abolishes all distinctions heretofore recognized between combatant and noncombatant enemies. If the United States should adopt it, then Napoleon’s saying, “Scratch a Russian (and) you will find a Tarter,” will not apply alone to the subjects of the Czar. In contrast with these pitiless doctrines that suggest the picture of the Infernal Court and “The iron tears that rain down Pluto’s cheek,” are the humane rules of international law as expounded by Professor Twiss, of Oxford, in his work on Rights and Duties in Time of War.

“All damage, therefore, which is done to an enemy without any corresponding advantage accruing to the belligerent is an abuse of a natural right of the latter. Thus, indeed, a belligerent is entitled to capture all the property of an enemy which is calculated to enable him the better to carry on hostilities, and if he cannot carry it away conveniently, to destroy it. A belligerent, for example, may destroy all existing stores of provisions and forage, which he cannot conveniently carry away, and may even destroy the standing crops, in order to deprive his enemy of immediate subsistence, and so reduce him to surrender. But a belligerent will not be justified in cutting the olive trees and rooting up the vines; for that is to inflict desolation upon a country for many years to come, and the belligerent cannot derive any corresponding advantage therefrom. When the French armies desolated with fire and sword the Palatinate in 1674 and again in 1689, there was a general outcry throughout Europe against such a mode of carrying on war; and when the French Minister, Louvol, alleged that the object in view was to cover the French frontier against invasion from the enemy, the advantage which France derived from the act was universally held to be inadequate to the suffering inflicted, and the act itself to be, therefore, unjustifiable.

“A belligerent prince who should, in the present day, without necessity, ravage an enemy’s country with fire and sword, and render it uninhabitable, in order to make it serve as a barrier against the advance of the enemy, would be just regarded as a modern Attila.”

It must be remembered that after the war, Mosby worked tirelessly to achieve true reconciliation. He wished the wrongs - real and perceived - on BOTH sides consigned to oblivion. As such he "made up" with men like Sheridan. However, as the new century commenced, Mosby began to see the true nature of the government that had prevailed in the war. Part of that was the numerous times in which his efforts to fulfill duties of justice to which he was assigned by the government by which he had been employed were thwarted by members of that same government, usually resulting in him being demoted, removed and re-assigned to some other area at less pay. In 1910 when he refused to cover up the theft of money from the Indians in Oklahoma after being offered a $35,000 bribe, he was fired from the Department of Justice and set adrift without money or a position. Mosby managed to support himself by writing and lecturing (he was let go because he was "senile!"), but died in poverty in 1916. By that time, however, I believe that he had finally understood why the South went to war. In the last sentence of his memoirs published posthumously, he stated that if he could have saved the Confederacy "with this right arm," he would have done so.

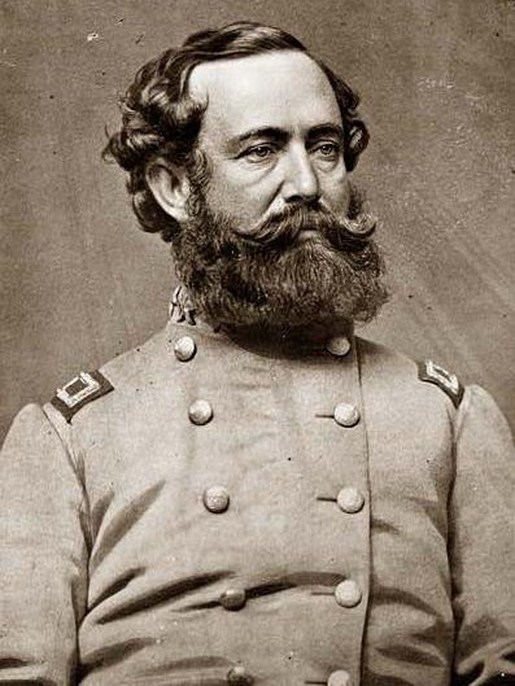

~ General Daniel Harvey Hill ~

Letter from D. H. Hill to Union General Foster

OFFICIAL RECORDS: Series 2, vol 5, Part 1 (Prisoners of War) p. 389-390

GOLDSBOROUGH, N. C., March 24, 1863.

Major General J. G. FOSTER, Federal Army.

SIR: Two communications have been referred to me as the successor of General French. The prisoners from Swindell’s company and the Seventh North Carolina are true prisoners of war and if not paroled I will retaliate five-fold. In regard to your first communication touching the burning of Plymouth you seem to have forgotten two things. You forget, sir, that you are a Yankee and that Plymouth is a Southern town. It is no business of yours if we choose to burn one of our own towns. A meddling Yankee troubles himself about everybody’s matters except his own and repents of everybody’s sins except his own. We are a different people. Should the Yankees burn a Union village in Connecticut or a cod-fish town in Massachusetts we would not meddle with them but rather bid them God-speed in their work of purifying the atmosphere. Your second act of forgetfulness consists in your not remembering that you are the most atrocious house-burner as yet unsung in the wide universe. Let me remind you of the fact that you have made two raids when you were weary of debauching in your negro harem and when you knew that your forces outnumbered the Confederates five to one. Your whole line of march has been marked by burning churches, school-houses, private residences, barns, stables, gin-houses, negro cabins, fences in the row, &c. Your men have plundered the country of all that it contained and wantonly destroyed what they could not carry off. Before you started on your free booting expedition toward Tarborough you addressed your soldiers in the town of Washington and told them that you were going to take them to a rich country full of plunder. With such a hint to your thieves it is not wonderful that your raid was characterized by rapine, pillage, arson and murder. Learning last December that there was but a single weak brigade on this line you tore yourself from the arms of sable beauty and moved out with 15,000 men on a grand marauding foray. You partially burned Kinston and entirely destroyed the village of White Hall. The elegant mansion of the planter and the hut of the poor farmer and fisherman were alike consumed by your brigands. How matchless is the impudence which in view of this wholesale arson can complain of the burning of Plymouth in the heat of action! But there is another species of effrontery which New England itself cannot excel. When you return to your harem from one of these Union-restoring excursions you write to your Government the deliberate lie that you have discovered a large and increasing Union sentiment in this State. No one knows better than yourself that there is not a respectable man in North Carolina in any condition of life who is not utterly and irrevocably opposed to union with your hated and hateful people. A few wealthy men have meanly and falsely professed Union sentiments to save their property and a few ignorant fishermen have joined your ranks but to betray you when the opportunity offers. No one knows better than yourself that our people are true as steel and that our poorer classes have excelled the wealthy in their devotion to our cause. You knowingly and willfully lie when you speak of a Union sentiment in this brave, noble and patriotic State. Wherever the trained and disciplined soldiers of North Carolina have met the Federal forces you have been scattered as leaves before t he hurricane.

In conclusion let me inform you that I will receive no more white flags from you except the one which covers your surrender of the scene of your lust, your debauchery and your crimes. No one dislikes New England more cordially than I do, but there are thousands of honorable men even there who abhor your career fully as much as I do.

Sincerely and truly, your enemy,

D. H. HILL,

Major-General, C. S. Army

OFFICIAL RECORDS: Series 2, vol 5, Part 1 (Prisoners of War) p. 389-390

GOLDSBOROUGH, N. C., March 24, 1863.

Major General J. G. FOSTER, Federal Army.

SIR: Two communications have been referred to me as the successor of General French. The prisoners from Swindell’s company and the Seventh North Carolina are true prisoners of war and if not paroled I will retaliate five-fold. In regard to your first communication touching the burning of Plymouth you seem to have forgotten two things. You forget, sir, that you are a Yankee and that Plymouth is a Southern town. It is no business of yours if we choose to burn one of our own towns. A meddling Yankee troubles himself about everybody’s matters except his own and repents of everybody’s sins except his own. We are a different people. Should the Yankees burn a Union village in Connecticut or a cod-fish town in Massachusetts we would not meddle with them but rather bid them God-speed in their work of purifying the atmosphere. Your second act of forgetfulness consists in your not remembering that you are the most atrocious house-burner as yet unsung in the wide universe. Let me remind you of the fact that you have made two raids when you were weary of debauching in your negro harem and when you knew that your forces outnumbered the Confederates five to one. Your whole line of march has been marked by burning churches, school-houses, private residences, barns, stables, gin-houses, negro cabins, fences in the row, &c. Your men have plundered the country of all that it contained and wantonly destroyed what they could not carry off. Before you started on your free booting expedition toward Tarborough you addressed your soldiers in the town of Washington and told them that you were going to take them to a rich country full of plunder. With such a hint to your thieves it is not wonderful that your raid was characterized by rapine, pillage, arson and murder. Learning last December that there was but a single weak brigade on this line you tore yourself from the arms of sable beauty and moved out with 15,000 men on a grand marauding foray. You partially burned Kinston and entirely destroyed the village of White Hall. The elegant mansion of the planter and the hut of the poor farmer and fisherman were alike consumed by your brigands. How matchless is the impudence which in view of this wholesale arson can complain of the burning of Plymouth in the heat of action! But there is another species of effrontery which New England itself cannot excel. When you return to your harem from one of these Union-restoring excursions you write to your Government the deliberate lie that you have discovered a large and increasing Union sentiment in this State. No one knows better than yourself that there is not a respectable man in North Carolina in any condition of life who is not utterly and irrevocably opposed to union with your hated and hateful people. A few wealthy men have meanly and falsely professed Union sentiments to save their property and a few ignorant fishermen have joined your ranks but to betray you when the opportunity offers. No one knows better than yourself that our people are true as steel and that our poorer classes have excelled the wealthy in their devotion to our cause. You knowingly and willfully lie when you speak of a Union sentiment in this brave, noble and patriotic State. Wherever the trained and disciplined soldiers of North Carolina have met the Federal forces you have been scattered as leaves before t he hurricane.

In conclusion let me inform you that I will receive no more white flags from you except the one which covers your surrender of the scene of your lust, your debauchery and your crimes. No one dislikes New England more cordially than I do, but there are thousands of honorable men even there who abhor your career fully as much as I do.

Sincerely and truly, your enemy,

D. H. HILL,

Major-General, C. S. Army

"Union General Piatt wrote in his book “Men Who Saved the Union” in 1887: “The true story of the late war has not yet been told. It probably never will be told. It is not flattering to our people; unpalatable truths seldom find their war into history.

How rebels fought the world will never know; for two years they kept an army in the field that girt their borders with a fire that shriveled our forces as they marched in, like tissue paper in a flame. Southern people were animated by a felling that the word fanaticism feebly expresses. (Love of liberty expresses it.) For two years this feeling held those rebels to a conflict in which they were invincible.

The North poured out its noble soldiery by the thousands and they fought well, but their broken columns and thinned lines drifted back upon our capitol, with nothing but shameful disasters to tell of the dead, the dying the lost colors and the captured artillery. Grant’s road from the Rapidan to Richmond was marked by a highway of human bones.

“We can lose five men to their one and win,” said Grant. The men of the South, half starved, unsheltered, in rags, shoeless yet Grant’s marches from the Rapidan to Richmond left dead behind him more men than the Confederates had in the Field!!!"

~ Union General Piatt ~

General John B. Gordon when addressing the women of York, Pennsylvania, about the arrival of his troops and their safety, said the following to them:

“Our southern homes have been pillaged sacked and burned; our mothers, wives, and little ones, driven forth amid the brutal insults of your soldiers. Is it any wonder that we fight with such desperation? Unnatural vengeance would prompt us to retaliate, but we scorn to war on women and children.”

Source: “Life and Letters of Robert Edward Lee: Soldier and Man,” by John William Jones, published 1906.

“Our southern homes have been pillaged sacked and burned; our mothers, wives, and little ones, driven forth amid the brutal insults of your soldiers. Is it any wonder that we fight with such desperation? Unnatural vengeance would prompt us to retaliate, but we scorn to war on women and children.”

Source: “Life and Letters of Robert Edward Lee: Soldier and Man,” by John William Jones, published 1906.

The Right To Secede

By Joseph Sobran

September 30, 1999

How can the federal government be prevented from usurping powers that the Constitution doesn’t grant to it? It’s an alarming fact that few Americans ask this question anymore.

Our ultimate defense against the federal government is the right of secession. Yes, most people assume that the Civil War settled that. But superior force proves nothing. If there was a right of secession before that war, it should be just as valid now. It wasn’t negated because Northern munitions factories were more efficient than Southern ones.

Among the Founding Fathers there was no doubt. The United States had just seceded from the British Empire, exercising the right of the people to “alter or abolish” — by force, if necessary — a despotic government. The Declaration of Independence is the most famous act of secession in our history, though modern rhetoric makes “secession” sound somehow different from, and more sinister than, claiming independence.

The original 13 states formed a “Confederation,” under which each state retained its “sovereignty, freedom, and independence.” The Constitution didn’t change this; each sovereign state was free to reject the Constitution. The new powers of the federal government were “granted” and “delegated” by the states, which implies that the states were prior and superior to the federal government.

Even in The Federalist, the brilliant propaganda papers for ratification of the Constitution (largely written by Alexander Hamilton and James Madison), the United States are constantly referred to as “the Confederacy” and “a confederate republic,” as opposed to a single “consolidated” or monolithic state. Members of a “confederacy” are by definition free to withdraw from it.

Hamilton and Madison hoped secession would never happen, but they never denied that it was a right and a practical possibility. They envisioned the people taking arms against the federal government if it exceeded its delegated powers or invaded their rights, and they admitted that this would be justified. Secession, including the resort to arms, was the final remedy against tyranny. (This is the real point of the Second Amendment.)

Strictly speaking, the states would not be “rebelling,” since they were sovereign; in the Framers’ view, a tyrannical government would be rebelling against the states and the people, who by defending themselves would merely exercise the paramount political “principle of self-preservation.”

The Constitution itself is silent on the subject, but since secession was an established right, it didn’t have to be reaffirmed. More telling still, even the bitterest opponents of the Constitution never accused it of denying the right of secession. Three states ratified the Constitution with the provision that they could later secede if they chose; the other ten states accepted this condition as valid.

Early in the nineteenth century, some Northerners favored secession to spare their states the ignominy of union with the slave states. Later, others who wanted to remain in the Union recognized the right of the South to secede; Abraham Lincoln had many of them arrested as “traitors.” According to his ideology, an entire state could be guilty of “treason” and “rebellion.” The Constitution recognizes no such possibility.

Long before he ran for president, Lincoln himself had twice affirmed the right of secession and even armed revolution. His scruples changed when he came to power. Only a few weeks after taking office, he wrote an order for the arrest of Chief Justice Roger Taney, who had attacked his unconstitutional suspension of habeas corpus. His most recent biographer has said that during Lincoln’s administration there were “greater infringements on individual liberties than in any other period in American history.”

As a practical matter, the Civil War established the supremacy of the federal government over the formerly sovereign states. The states lost any power of resisting the federal government’s usurpations, and the long decline toward a totally consolidated central government began.

By 1973, the federal government was so powerful that the U.S. Supreme Court could insult the Constitution by striking down the abortion laws of all 50 states; and there was nothing the states, long since robbed of the right to secede, could do about it. That outrage was made possible by Lincoln’s triumphant war against the states, which was really his dark victory over the Constitution he was sworn to preserve.

By Joseph Sobran

September 30, 1999

How can the federal government be prevented from usurping powers that the Constitution doesn’t grant to it? It’s an alarming fact that few Americans ask this question anymore.

Our ultimate defense against the federal government is the right of secession. Yes, most people assume that the Civil War settled that. But superior force proves nothing. If there was a right of secession before that war, it should be just as valid now. It wasn’t negated because Northern munitions factories were more efficient than Southern ones.

Among the Founding Fathers there was no doubt. The United States had just seceded from the British Empire, exercising the right of the people to “alter or abolish” — by force, if necessary — a despotic government. The Declaration of Independence is the most famous act of secession in our history, though modern rhetoric makes “secession” sound somehow different from, and more sinister than, claiming independence.

The original 13 states formed a “Confederation,” under which each state retained its “sovereignty, freedom, and independence.” The Constitution didn’t change this; each sovereign state was free to reject the Constitution. The new powers of the federal government were “granted” and “delegated” by the states, which implies that the states were prior and superior to the federal government.

Even in The Federalist, the brilliant propaganda papers for ratification of the Constitution (largely written by Alexander Hamilton and James Madison), the United States are constantly referred to as “the Confederacy” and “a confederate republic,” as opposed to a single “consolidated” or monolithic state. Members of a “confederacy” are by definition free to withdraw from it.

Hamilton and Madison hoped secession would never happen, but they never denied that it was a right and a practical possibility. They envisioned the people taking arms against the federal government if it exceeded its delegated powers or invaded their rights, and they admitted that this would be justified. Secession, including the resort to arms, was the final remedy against tyranny. (This is the real point of the Second Amendment.)

Strictly speaking, the states would not be “rebelling,” since they were sovereign; in the Framers’ view, a tyrannical government would be rebelling against the states and the people, who by defending themselves would merely exercise the paramount political “principle of self-preservation.”

The Constitution itself is silent on the subject, but since secession was an established right, it didn’t have to be reaffirmed. More telling still, even the bitterest opponents of the Constitution never accused it of denying the right of secession. Three states ratified the Constitution with the provision that they could later secede if they chose; the other ten states accepted this condition as valid.

Early in the nineteenth century, some Northerners favored secession to spare their states the ignominy of union with the slave states. Later, others who wanted to remain in the Union recognized the right of the South to secede; Abraham Lincoln had many of them arrested as “traitors.” According to his ideology, an entire state could be guilty of “treason” and “rebellion.” The Constitution recognizes no such possibility.

Long before he ran for president, Lincoln himself had twice affirmed the right of secession and even armed revolution. His scruples changed when he came to power. Only a few weeks after taking office, he wrote an order for the arrest of Chief Justice Roger Taney, who had attacked his unconstitutional suspension of habeas corpus. His most recent biographer has said that during Lincoln’s administration there were “greater infringements on individual liberties than in any other period in American history.”

As a practical matter, the Civil War established the supremacy of the federal government over the formerly sovereign states. The states lost any power of resisting the federal government’s usurpations, and the long decline toward a totally consolidated central government began.

By 1973, the federal government was so powerful that the U.S. Supreme Court could insult the Constitution by striking down the abortion laws of all 50 states; and there was nothing the states, long since robbed of the right to secede, could do about it. That outrage was made possible by Lincoln’s triumphant war against the states, which was really his dark victory over the Constitution he was sworn to preserve.

"We are the last of our race. Let us be the best as well."

~General Joseph O. Shelby ~